A conservation variation for the Ethiopic binding

Following a strong wish to deepen my knowledge of non-Western bookbindings, both to widen my experience as a conservator and to guide my conservation treatment choices for these objects, I was very lucky to attend one of the four courses offered by The Montefiascone Conservation Project this year. This five-day workshop focused on the study of the traditional Ethiopic book structure, including an introduction to some unique materials used in Ethiopia for bookbinding. The course was set in the Italian town of Montefiascone in the province of Viterbo, about 75 miles North of Rome. Our class was composed of 12 students from different countries – including the UK, Australia, Sweden and the USA.

- Montefiascone

- The Seminary Barbarigo

- The Lake Bolsena

The first part of the course involved presentation of the project Ethio-SPaRe: Cultural Heritage of Christian Ethiopia, Salvation, Preservation and Research by the tutors of the course. This interdisciplinary project (2009-2015) aimed at preserving the Ethiopian culture by studying, recording, cataloguing and digitising manuscripts from monasteries and churches. The Ethiopian bookbinding tradition is still very lively nowadays and has not changed for hundred of years; books are still produced by scribes and bookbinders in the exact same way for centuries. During the project, multiple Ethiopian binding characteristics were surveyed and studied, and some of the books conserved.

- Students and tutors ready for the course © The Montefiascone Conservation Project

- Presentation of the Ethio-Spare project

The second practical part of the course included the creation of two book-models; a traditional Ethiopic structure and a model based on the conservation binding designed by the tutors for the treatment of a 15th century parchment manuscript in Ethiopia.

Traditionally, Ethiopian bindings are produced by the scribes, who take care of the whole bookbinding process. Made of parchment solely, the text blocks are bound over boards, usually made of wanza, a locally available wood. The parchment sections are sewn using a collagen based thread, “gut-thread”, made from animal intestines or tendons which are twisted on themselves. The books are sewn using a link-stitch pattern, without any supports. The binding process is completed after fully covering the book with leather, and attaching the endbands, traditionally made with braided leather strips. The leather cover is lastly ornamented with blind-tooling patterns. Our first model followed this tradition, with some small variations due to cost restrictions and ease of access to materials.

- Measuring and marking the sewing stations on the text block

- Completed sewing and upper board attached

- Completed bookmark

- Adhering the textile inside the boards

- Choosing Egyptian leather for covering © Montefiascone project

- Covering the book-model with red leather

- Leather strips and basketry awl

- Attaching the braided endbands, sewing through the middle of each section and the braid

- Tooling in progress, using traditional Ethiopian tools

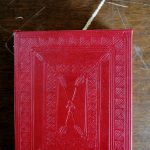

- Tooling completed

Our conservation model included some variations in the binding structure; while being historically respectful of the Ethiopic bindings, they aimed at the improvement of the conservation of these types of books. Similarly sewn on wooden boards, the structure is reinforced by the addition of a “spine stiffener” made of a layer of alum-tawed and parchment. Completely adhesive free, this additional material is sewn with the sections. The spine stiffener helps to support the spine, sewing structure, and opening characteristics of the book, which are weakness points in Ethiopic bindings. Plain coloured leather braided endbands were attached as further reinforcement and completed the binding.

- Conservation model example

- Sewing the spine stiffener to the boards

- Attaching the boards

- Attaching the braided endband to the text block

- Coptic endband sewn to the book

Finally, all participants were able to create a traditional manuscript satchel. This square or rectangular bag in parchment is traditionally used to protect the textblock and keep it under the necessary pressure, while also facilitating storage and transport. Our satchel was made of two pieces of parchment cut and folded, which were sewn with thin parchment strips and thick needles. Again, the structure was completely adhesive-free.

- Ethiopian satchel example

- Assembling the parchment for the satchel

While practicing my bookbinding skills, The Montefiascone Project allowed me to study the Ethiopic book structure and to understand the possible conservation applications for these bindings. Creating an historic book model plays an important role in the conservator’s work, as it allows a better understanding of the mechanics of the book, an essential point when returning it to mechanical functionality. Consequently I hope this will inform my preservation and conservation treatment decisions when confronted to similar objects. These skills are also adaptable and transferable to other structures than the Ethiopic book, and I am looking forward to putting my new knowledge into practice and sharing it with colleagues.

- Gelateria artisanale, Montefiascone

- Sunset on the Lake Bolsena

I am grateful to the Anna Plowden Trust and the Clothworkers Foundation and the Zibby Garnett Travel Fellowship for their generous contribution to the funding of this course, which made my attendance possible. It was a wonderful experience and I hope to attend the Summer School again in the following years!

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post