Sacred tradition of India – A Sikh binding of the 18th century

“The sacred codex is the abode of the supreme being…” Guru Arjan Dev Ji, Adi Guru Granth Sahib

It is in a small medieval town in the North of Rome, in Italy, that we will talk about India. Montefiascone, high above Lake Bolsena in Lazio, holds for another year the Montefiascone Conservation Project.

The project was founded in 1988 by Cheryl Porter, who now directs the project. Every year, four courses look at the history of the book, gathering conservators, curators, art historians, bookbinders and book lovers from all over the world under the Italian sunshine.

- Montefiascone

- The Seminario Barbarigo

- Lake Bolsena

This year the five-day course I had the chance to attend studied the Sikh manuscript tradition. Taught by Jasdip Singh Dhillon and Sukhraj Singh, the course introduced participants to the history of the Sikh codex making tradition, which developed from the 15th century in the Panjab region of South Asia. Sikh bindings are the results of various influences, such as the birch bark and palm leaves codices, but also include Islamic and European binding characteristics.

- Introduction to the history of the Sikh codex making tradition

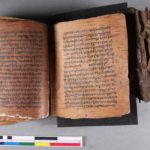

- BL OMS/Or 13300, Kashmir, Śāradā script, 16-17th century. Reproduced with kind permission of The British Library

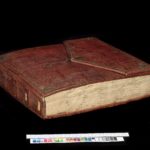

- A mid-19th century Sikh manuscript. Reproduced with kind permission of Bodleian Libraries

Sikh codices are worshiped as the living representation of the Guru, which confers to the manuscripts a unique aspect. As conservators, understanding the Sikh worship and preservation practices was invaluable. Through photos and videos, Jasdip and Sukhraj explained how the Sikh faith is linked to the book, sharing documentary footage of the morning and evening rituals of the presentation of the book to the temple.

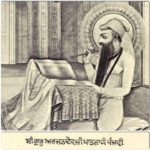

- Print from 1909 showing the fifth Guru, Guru Arjan Dev with a manuscript supported with cushions. Source: Macauliff, M.A., The Sikhs, 1909

- Harmandir, The “Golden Temple of Amritsar” is the most sacred site in Sikhism. © Sarah Welch

- The “Golden Temple of Amritsar” islocated in the city of Amritsar. © Amritpal Singh Mann

The binding model we created is a scaled down model based on two bindings from the mid-18th century. The first book is kept in the Guru Nanak Dev University collection (MSG 98) in India, the second is part of the British Library collection (MS Panj.d3). Both are Adi Guru Granth Sahib manuscripts, the Sikh scripture, which is the spiritual authority in Sikhism. Compiling verses by the founders of Sikhism and saints, the book is considered as the last and eternal living guru.

- MSG98 ( Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar). Image reproduced with kind permission of The Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar

- MS Panj. D 3 (British Library). Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Library

Before the course, our model started with the preparation of the textblock, using a relatively soft cream coloured paper of around 100gsm. We prepared 30 sections each made up of 4 bifolia. Traditionally, two sets of two black lines were drawn on the left and right margins, to delineate the text area of the page. On the first day of the course, Jasdip demonstrated ruling margins in this palm-leaf style using a ruling pen and black ink. In later manuscripts, variations in colour and number of rulings appeared, with also the ruling at the head and tail margins.

- Course materials ready, including the textblock, leather, pasteboards and fabric

- Demonstrating ruling margins

Next, Jasdip demonstrated the creation of silk quire tackets, placed at head and tail along the spine of each quire. These tackets facilitate the binding process by preventing the bifolia from slipping over one another during sewing. They also allow multiple scribes to work on the same manuscript, as each gathering acts as a little booklet on its own.

After tacketing, it was time for sewing! For this purpose, a cream coloured silk thread was used following a loop-stitch pattern.

- Creation of silk quire tackets

- Measuring and marking the sewing station on the textblock

- Sewing the textblock in progress

- Sewing the textblock in progress

- Completed loop-stitched sewing

The spine was then reinforced with two pasteboard spine stiffeners, pasted over the sewing stations. These stiffeners are visually similar to Western sewing supports, however in this case they act to restrict the movement of the spine and protect the fragile sewing. A textile lining made of cotton calico and covering the full length of the spine, was then adhered over the spine and the stiffeners.

- Adhering the pasteboard spine stiffener

- Spine stiffeners adhered on the spine

- Jasdip demonstrating lining the spine

- Pasting the cotton calico fabric

- Adhering the textile cotton calico over the spine

Next, metallic twined endbands were sewn over rolled cotton cores, using metallic and cotton threads for the decorative secondary endband, alongside silk coloured thread for the primary endband.

- Preparation of the rolled cotton cores

- Sewing the primary endbands

- Sewing the secondary endbands

- Sewing the secondary endbands

- Sewing the secondary endbands

- Secondary endbands completed

The board, envelope flap and foredge pieces were then prepared and cut to size. The boards are slightly narrower than the textblock, while the flap is cut so that the point sits at the centre of the upper board. The leather for covering was then cut to size and pared down along the spine area and the edges. Our boards were covered in two pieces: firstly, the upper board; and then the lower board, foredge piece and flap.

Once the boards were covered, the leather was turned in along all edges except the spine, and the leather doublures adhered. After drying, the boards were attached to the textblock using the spine edge extension of both boards to overlap on the spine, as has been seen in Islamic bindings. Great care was taken to mould the leather perfectly around the spine stiffeners.

- Students and tutors carefully working on their binding

- Preparation of the enveloppe flap

- Paring the leather along the edges, using a semi-circular knife

- Jasdip demonstrating covering the lower board

- Covering the upper board, ready to paste the leather doublures

- Covering the lower board in progress

- Turning the leather in, making sure the leather will dry under pressure

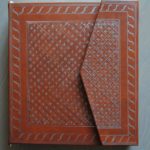

The painted decoration of the leather cover could then begin! On this model, the decoration is kept simple, with silver repeated motives painted on the boards and envelope flap. We used a sympathetic coloured silver acrylic paint, tracing the decorative lines with a ruling pen and painting the small flowers with a thin brush.

- Painting decoration in progress. © Annemarie Kloeg

- Painting decoration in progress, using silver-coloured acrylic paint

- Painting decoration in progress

- Measuring before painting!

Due to their high spiritual value, Sikh bindings are greatly cared for. To offer the binding further protection, a traditional textile over-garment usually wraps the book completely, covering the boards but also including extended endband tabs which protect the textblock edges. We used a soft pink cotton to make the main over-garment, with the addition of a beautiful flowery printed textile on the inner part of the endband tabs. The sewing was made with a soft gold-coloured silk thread.

- Measuring the fabric necessary for the over-garment

- Securing and hemming the fabric edges

- Sewing the fabric around the enveloppe flap

- Sewing the edge straps with a running stitch

- Placing pins on the spine, marking where to attach the edge strap

- Preparing one of the edge straps

- Attaching the edge strap

This year once again Montefiascone allowed me to learn about a new book structure, but also about the faith and the practices embedded with those beautiful Sikh bindings. This course has also been a wonderful opportunity for me to exchange and share bookbinding skills and to meet professionals in the field. I am now looking forward to sharing my experiences and putting my new knowledge into practice!

- All the students proudly showing their completed binding! © The Montefiascone Conservation Project

- Completed model

- Completed model

- Completed model

- Completed model

I wish to thank Cheryl Porter, Jasdip Singh Dhillon, Sukhraj Singh and Karanveer Singh Rai for teaching this inspiring course. I am grateful to Pothi Seva for their contribution to the funding of this course, which made my attendance possible.

Previous Post

Previous Post